State Laws on NTI Drug Substitution: What Pharmacists and Patients Need to Know in 2026

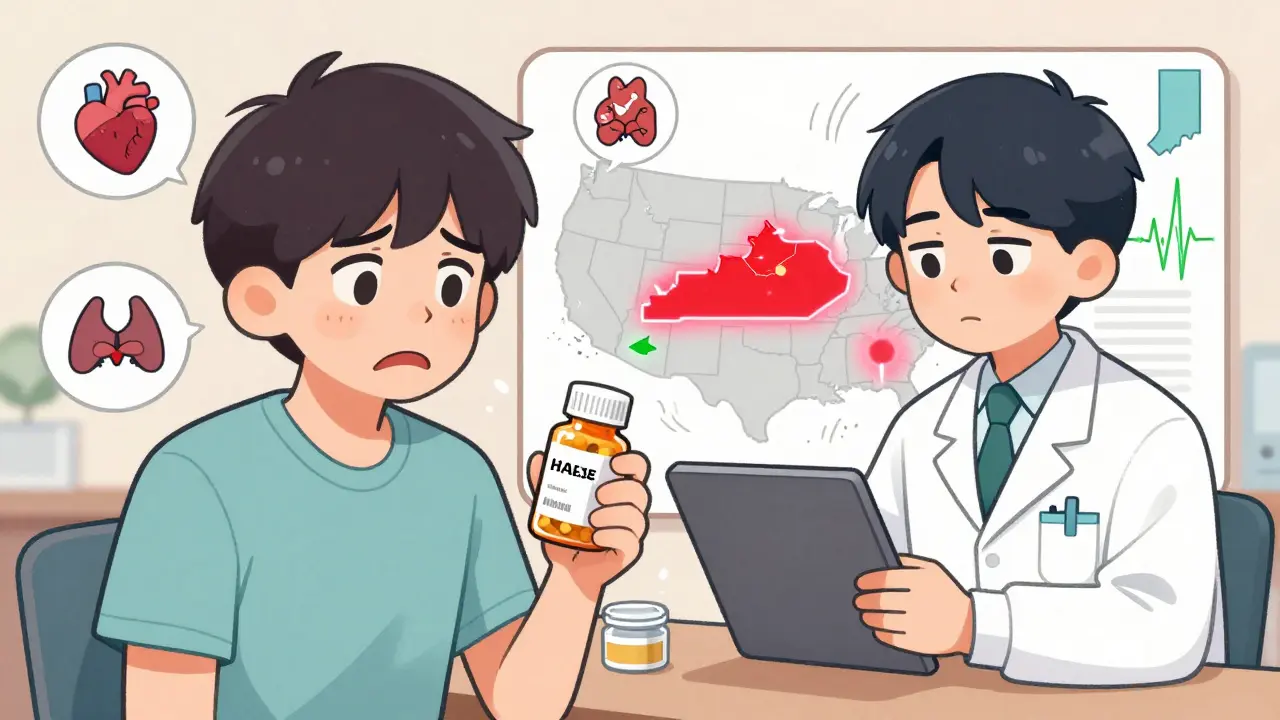

When you take a medication like warfarin, levothyroxine, or phenytoin, even a tiny change in dose can mean the difference between being safe and ending up in the hospital. These are NTI drugs - Narrow Therapeutic Index drugs - where the gap between an effective dose and a dangerous one is razor-thin. You might not know it, but whether your pharmacist can swap your brand-name pill for a cheaper generic depends on which state you live in. And the rules? They’re a mess.

What Exactly Are NTI Drugs?

NTI drugs are medications where even a 5% to 10% change in blood concentration can cause serious harm. Too little, and the drug doesn’t work. Too much, and you risk toxicity. Think of it like driving a car with no speedometer - you’re guessing how fast you’re going, and one wrong turn could crash you into a wall.

Examples include:

- Warfarin (blood thinner)

- Levothyroxine (thyroid hormone)

- Phenytoin, carbamazepine (anti-seizure meds)

- Lithium (mood stabilizer)

- Digoxin (heart medication)

The FDA doesn’t officially label any drug as NTI in its Orange Book - the public database that rates drug equivalence. But that doesn’t mean these drugs aren’t dangerous. In fact, the FDA itself created a list of NTI candidates back in 1995, even though it never made it public policy. That contradiction is at the heart of the whole problem.

Why Do States Step In When the FDA Doesn’t?

The FDA says bioequivalence standards - the 80% to 125% range used to approve generic drugs - are good enough for everything, even NTI drugs. But doctors and pharmacists see what happens in real life. A 2023 meta-analysis of 17 studies found that over one-third of patients stabilized on brand-name levothyroxine had to adjust their dose after switching to a generic. Their TSH levels jumped or dropped, sometimes triggering heart problems, anxiety, or fatigue.

States noticed. By 2024, 27 states had passed laws restricting substitution of NTI drugs. Some outright ban it. Others require doctors to write "do not substitute" on prescriptions. A few just recommend caution. The result? A patchwork of rules that makes pharmacy work in multiple states nearly impossible.

How States Differ: From Bans to Recommendations

Let’s look at how five states handle it:

- Kentucky: Has a formal list. No substitution allowed for digitalis, antiepileptics, or warfarin. Pharmacists must check the list before dispensing.

- Pennsylvania: Also has a list. Same drugs as Kentucky. Violating it can mean fines or license suspension.

- South Carolina: Doesn’t ban substitution - but strongly recommends against it for NTI drugs, plus insulin, asthma inhalers, and Synthroid. Pharmacists can still substitute, but they’re expected to know the risks.

- Tennessee: Allows substitution for most A-rated generics - except for antiepileptics in patients with epilepsy. Even then, if the patient’s doctor didn’t specify "dispense as written," the pharmacist can swap it. But if the patient has seizures? No swap. Period.

- California: Defines "critical dose drugs" as those where a 10% blood level change could be dangerous. Pharmacists must notify the prescriber before substituting any drug on that list. It’s not a ban - it’s a mandatory check-in.

And then there’s Iowa. Instead of making its own list, the state tells pharmacists to use the FDA’s Orange Book. But here’s the catch - the Orange Book doesn’t mark NTI drugs. So pharmacists in Iowa are left guessing.

The Real Cost of Confusion

Imagine you’re a pharmacist working for a chain that spans three states. You fill a prescription for warfarin in Ohio - no substitution allowed. Then you switch to your shift in Indiana - substitution is fine. Then you cover a weekend shift in Kentucky - now you’re back to the banned list. You’re tired. You’re rushed. You miss the difference.

A 2023 survey by the National Community Pharmacists Association found that 68% of pharmacists who work across state lines have been confused about substitution rules. Over 40% admitted they accidentally broke a law in the past year. That’s not incompetence. That’s a broken system.

And it’s not just pharmacists. Patients get caught in the middle. Someone on stable levothyroxine gets switched to a generic without knowing. Their TSH spikes. They lose weight, feel anxious, and their heart races. They go to the ER. The doctor asks, "Did you change meds?" They say, "No, I just picked it up like always." The pharmacist says, "I followed the law." Who’s at fault?

What’s Changing in 2026?

Pressure is building. In September 2024, the FDA announced it would reconsider its stance on NTI drugs after the Senate Committee on Aging cited a Government Accountability Office report: 2,847 adverse events linked to NTI substitutions between 2019 and 2023. That’s not a glitch. That’s a pattern.

The National Association of Boards of Pharmacy rolled out the Model State NTI Substitution Act in January 2024. It proposes one national list of NTI drugs, based on clinical evidence, not state politics. Twelve states have already introduced it as legislation. If it passes, we could see a standardized list by 2027.

But there’s a trade-off. The same study predicting this change also warns that generic use for NTI drugs could drop by 8.3 percentage points. That means higher costs - for patients, insurers, and the system. But is safety worth the price? Most doctors and patients say yes.

What Should You Do as a Patient?

If you take an NTI drug, don’t assume your pharmacy will tell you if a switch happens. Ask. Always.

- Ask your pharmacist: "Is this the same brand I’ve been taking?"

- Ask your doctor: "Can you write ‘dispense as written’ on my prescription?"

- Check your pill bottle. Brand names are printed on the label. If it changed, and you didn’t approve it - call your pharmacy.

Some states require pharmacists to notify you if they switch your med. Others don’t. Don’t rely on them to tell you. Be your own advocate.

What Should Pharmacists Do?

If you’re licensed in multiple states, keep a printed or digital cheat sheet of each state’s NTI rules. Update it every quarter. Bookmark the NABP’s state-by-state guide. Use your pharmacy software to flag NTI prescriptions - but don’t rely on automation alone. Double-check.

When in doubt, don’t substitute. Call the prescriber. It takes 30 seconds. It could save a life.

And if you’re part of a chain pharmacy? Push for centralized training. This isn’t just compliance - it’s patient safety. And if your company won’t act? Document everything. You’re the last line of defense.

The Bigger Picture

Generic drugs saved the U.S. healthcare system $1.67 trillion between 2009 and 2022. That’s huge. But NTI drugs make up less than 2.3% of all prescriptions. So why are they causing so much trouble?

Because for these drugs, the math doesn’t add up. A 20% variation in bioequivalence might be fine for an antibiotic. It’s not fine for a blood thinner. The FDA’s one-size-fits-all approach is outdated. States are trying to fix it - but they’re doing it alone.

Until we get a national standard, patients and pharmacists will keep paying the price. And every time a pharmacist makes a mistake - or a patient gets sick - it’s not because someone was careless. It’s because the system was broken.

Are all generic drugs safe to substitute for NTI medications?

No. While most generic drugs are safe and effective, NTI drugs like warfarin, levothyroxine, and phenytoin have very narrow safety margins. Even small differences in how the body absorbs a generic version can lead to dangerous side effects or treatment failure. Many states restrict or prohibit substitution for these drugs, and patients should always confirm with their pharmacist or prescriber before switching.

Does the FDA officially list which drugs are NTI?

No. The FDA does not formally designate or label any drugs as Narrow Therapeutic Index in its Orange Book or other public databases. While the agency identified a list of potential NTI candidates in 1995, it never made that list official or public. This leaves states to create their own definitions, leading to inconsistent rules across the country.

Can a pharmacist substitute an NTI drug without the doctor’s permission?

It depends on the state. In states like Kentucky and Pennsylvania, substitution is banned outright for certain NTI drugs, regardless of the prescriber’s instructions. In others, like Tennessee, substitution is allowed unless the drug is an antiepileptic for a patient with epilepsy. In California, pharmacists must notify the prescriber before substituting any critical dose drug. Always check your state’s pharmacy board rules.

Why do some states allow substitution while others don’t?

The difference comes down to how each state balances cost savings with patient safety. States with stricter rules - like Kentucky and California - prioritize minimizing risk for vulnerable patients. States with looser rules often follow the FDA’s stance that generic bioequivalence standards are sufficient. The lack of federal guidance has forced states to act on their own, creating a confusing patchwork of laws.

What should I do if my NTI medication was switched without my knowledge?

Contact your pharmacist immediately to confirm the change. Then call your prescriber to report it - even if you feel fine. Some side effects from an NTI drug switch can take days or weeks to appear. Your doctor may need to order a blood test (like TSH for thyroid meds or INR for warfarin) to check if your levels are stable. Document everything: the date, the drug name, and who you spoke with.

Kunal Majumder

January 11, 2026 AT 14:59Been there. My grandma was on warfarin and got switched to a generic without warning. She ended up in the ER with a weird bruise on her thigh. We didn’t even know it happened until we saw the pill bottle. Always ask. Always check. Simple as that.

Aurora Memo

January 11, 2026 AT 21:06I appreciate how this post breaks down the state-by-state mess without sounding alarmist. It’s frustrating that patients have to be their own pharmacists, but honestly? That’s the reality now. I’ve told my patients to write ‘DAW’ on every NTI script - it’s the only thing that sticks.

chandra tan

January 13, 2026 AT 00:35In India we don’t even have this problem - generics are everywhere, and no one checks. But I’ve seen people on levothyroxine here go from fine to exhausted in a week after switching. It’s wild how the same drug can be treated like candy in one place and a bomb in another.

Dwayne Dickson

January 13, 2026 AT 05:14Let’s be clear: the FDA’s refusal to classify NTI drugs is not an oversight - it’s a corporate concession masked as regulatory efficiency. The bioequivalence paradigm was designed for antibiotics, not anticoagulants. To pretend otherwise is not just negligent - it’s an affront to clinical pharmacology. The state patchwork is tragic, but it’s the only functional response to institutional failure.

Ted Conerly

January 14, 2026 AT 00:29If you’re a pharmacist reading this - keep that cheat sheet updated. If you’re a patient - ask before you leave the counter. If you’re a doctor - write ‘dispense as written’ in big letters. This isn’t rocket science. It’s basic safety. And yeah, it’s on all of us to make it happen.

Faith Edwards

January 15, 2026 AT 20:39It is nothing short of a moral abdication that we allow the commodification of life-sustaining therapeutics to be dictated by state legislatures whose understanding of pharmacokinetics is roughly equivalent to their grasp of quantum mechanics. The fact that Iowa relies on the FDA’s non-existent NTI list is not incompetence - it is a grotesque parody of governance. I shudder to think what the next generation will inherit.

Michael Marchio

January 16, 2026 AT 12:14Look, I get that people are scared of generics, but let’s not turn this into a horror movie. The FDA’s standards are solid. If your TSH jumps after switching levothyroxine, maybe your body just needs time to adjust. Or maybe you’re one of those people who think every change is a conspiracy. I’ve seen patients panic over a different pill color. It’s not the drug - it’s the narrative.

Jake Kelly

January 18, 2026 AT 00:15My mom’s on lithium. She switched generics once and spent a week crying in bed. We called the pharmacy. They said it was ‘FDA-approved.’ I told them to call her psychiatrist. That’s when they realized they didn’t even know what lithium was for. We’re all just winging it.

Ashlee Montgomery

January 19, 2026 AT 13:57Why do we assume safety and cost must be enemies? What if we designed a system where generics were only allowed if they met stricter bioequivalence thresholds for NTI drugs? Not bans. Not chaos. Just better science. The tools exist. The will doesn’t.

neeraj maor

January 21, 2026 AT 06:21They’re lying. The FDA has the list. They just don’t want you to know. Big Pharma owns the Orange Book. They’ve been quietly pushing generics for NTI drugs for years because they make more money off the brand-name versions anyway. The states are just distractions. The real game is in the stock market. You think this is about safety? Look at the quarterly reports.

Ritwik Bose

January 21, 2026 AT 13:05Thank you for this detailed breakdown 🙏. As someone who works in pharmacy across two states, I’ve seen the confusion firsthand. I keep a printed copy of each state’s NTI rules in my locker. I’ve also started using the NABP guide on my phone. Small steps, but they matter. Let’s hope the Model Act passes soon 🤞.

lisa Bajram

January 23, 2026 AT 10:19Okay, real talk: I’m a pharmacist in Texas, and I just got certified in California last month. I spent 3 hours last week trying to figure out if I could swap carbamazepine for a patient who moved from Tennessee. I called the doctor. I called the state board. I cried in the supply closet. This isn’t healthcare - it’s a labyrinth designed by drunk bureaucrats. And yet? I still show up. Because someone’s gotta be the adult in the room. Don’t let the chaos win.