Gout: Understanding Purine Metabolism and How Urate-Lowering Medications Work

When your big toe swells up out of nowhere, burning like fire and too tender to even touch a sheet, it’s not just bad luck-it’s gout. This isn’t ordinary joint pain. It’s your body’s immune system attacking uric acid crystals that have formed in your joint, and those crystals? They’re the end result of how your body breaks down purines. Most people think gout is just about eating too much steak or drinking too much beer. But the real story runs deeper-into your cells, your genes, and the enzymes that control how your body handles waste. And if you’re on medication for it, you need to know exactly how those pills work, why some help and others don’t, and what your doctor isn’t always telling you.

What Happens When Purines Go Wrong

Purines are natural compounds found in nearly every cell in your body. They’re part of DNA and RNA, and they help your cells produce energy. When those cells die or get broken down, purines get processed into uric acid. In most animals, an enzyme called uricase turns uric acid into something harmless that’s easily flushed out. But humans lost that enzyme millions of years ago. So we’re stuck with uric acid as the final product.Normally, your kidneys filter out about 65% of your uric acid, and the rest leaves through your gut. But if your body makes too much, or your kidneys don’t clear enough, uric acid builds up. At levels above 6.8 mg/dL, it starts to crystallize-like salt in seawater. Those crystals settle in joints, especially the big toe, ankles, and knees. When your immune system spots them, it triggers a violent inflammatory response. That’s the flare.

Here’s the catch: you don’t need to feel a flare to have high uric acid. Many people have levels above 8 mg/dL for years without symptoms. But once crystals form, they stay. And each flare makes it more likely the next one will be worse. That’s why doctors don’t just treat the pain-they treat the underlying cause: hyperuricemia.

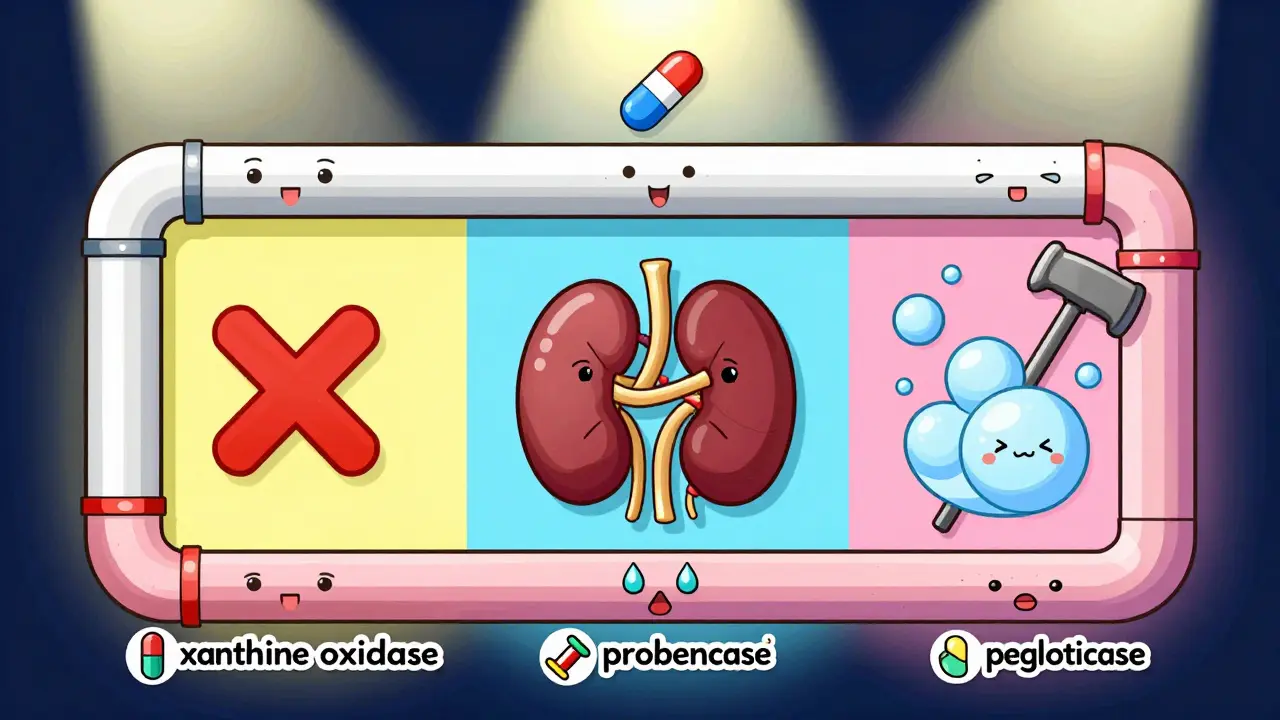

The Three Types of Urate-Lowering Medications

There are only three real ways to lower uric acid long-term: block its production, boost its removal, or break it down completely. Each approach has its own drugs, pros, cons, and risks.Xanthine oxidase inhibitors (XOIs) stop your body from making uric acid in the first place. They block the enzyme xanthine oxidase, which turns xanthine into uric acid. Two drugs dominate this category: allopurinol and febuxostat.

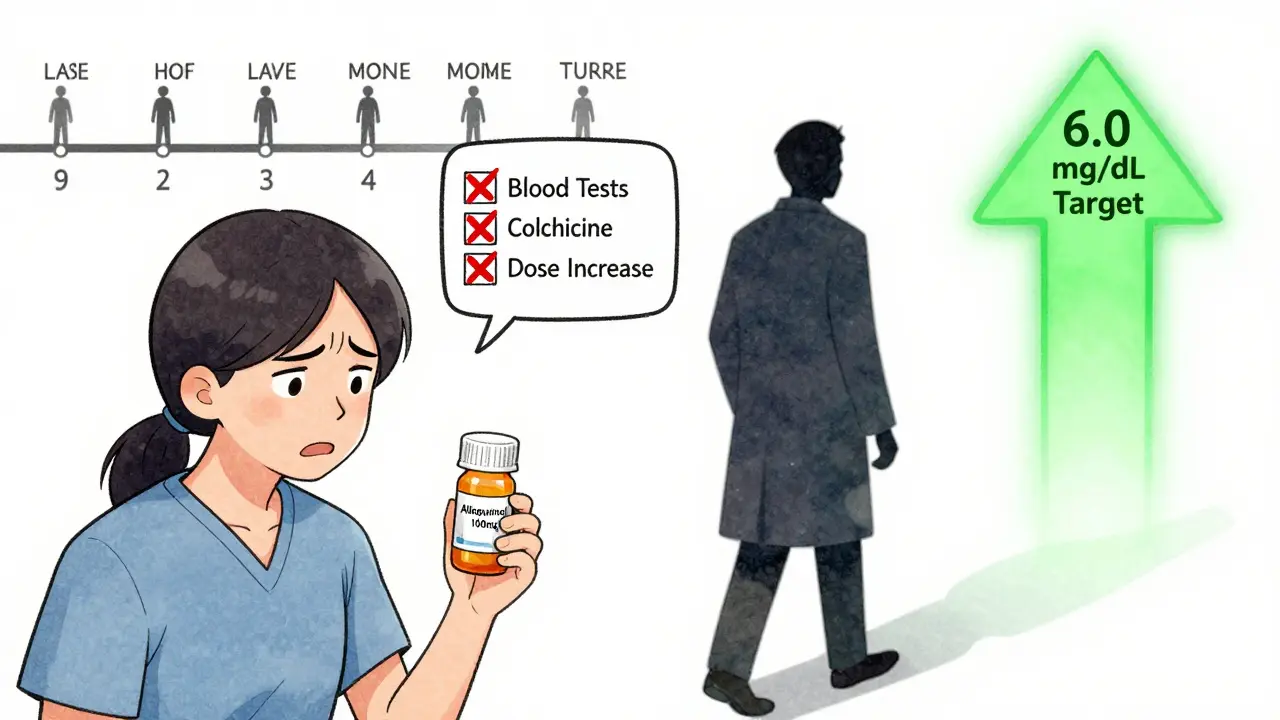

Allopurinol has been around since the 1960s. It’s cheap-generic versions cost less than $5 a month. But it doesn’t work for everyone. About half of patients need to take 300 mg or more daily to reach target levels. Many doctors start at 100 mg and never increase it, which is why so many people think it doesn’t work. The truth? If you’re not hitting uric acid levels below 6.0 mg/dL, you’re not on a high enough dose. Studies show 92% of patients reach target when allopurinol is properly titrated.

Febuxostat is newer and stronger. At 80 mg a day, it gets 67% of patients to target, compared to 47% with allopurinol. But it comes with a black box warning from the FDA. The CARES trial found it increased the risk of heart-related death in people with existing cardiovascular disease. If you have heart problems, your doctor should think twice before prescribing it.

Uricosurics help your kidneys flush out more uric acid. They work by blocking URAT1, a transporter that normally reabsorbs uric acid back into your blood. Probenecid is the classic drug here-approved in 1949. But it only works if your kidneys are still functioning well. If your creatinine clearance is below 50 mL/min, it’s useless. And it can cause kidney stones if you’re not drinking enough water.

Lesinurad was a newer option, designed to be taken with allopurinol. It pushed target attainment to 54%. But it was pulled from the market in 2019 because it damaged kidneys in some patients. Now, a new drug called verinurad is in late-stage trials and may bring back this approach safely.

Uricase agents are the nuclear option. Pegloticase breaks down uric acid into allantoin, a substance your body clears easily. It’s powerful-most patients see their tophi (those chalky lumps under the skin) shrink or disappear within a year. But it’s also expensive: over $16,000 a month. And it’s not for everyone. About 26% of people have severe infusion reactions. You need to be pre-treated with steroids and antihistamines. Plus, you must be tested for HLA-B*58:01, a genetic marker that increases the risk of life-threatening allergic reactions. If you’re positive, you can’t use it.

Why Most People Stop Taking Their Meds

You’d think that with all these options, gout would be under control. But here’s the hard truth: 61% of people stop taking their urate-lowering meds within a year. Why?First, they don’t feel better right away. In fact, they often feel worse. Starting allopurinol or febuxostat can trigger flares because the crystals are dissolving and stirring up inflammation. Most doctors don’t warn patients about this. The American College of Rheumatology says you should take colchicine (0.6 mg once or twice a day) for at least six months when starting treatment. But only 29% of primary care doctors actually do this.

Second, side effects scare people off. Allopurinol causes a rash in 12% of users-and for some, that rash turns into a deadly skin reaction called Stevens-Johnson syndrome. Febuxostat can raise liver enzymes. Probenecid causes kidney stones. Pegloticase? You need a nurse to give it, and you have to sit in a clinic for hours every two weeks.

Third, the system isn’t built for long-term management. Most patients see their primary care doctor once a year. But to make these drugs work, you need blood tests every 2-5 weeks until your uric acid hits target. Then every six months after that. Few clinics have the time or resources to track that. So patients get a prescription and are left to figure it out on their own.

What You Can Do Right Now

Diet helps-but not as much as you think. Cutting out beer and liver might lower your uric acid by 1-2 mg/dL. That’s helpful, but not enough. Anchovies have 500 mg of purines per 100 grams. Sardines? 300 mg. Organ meats? 240-400 mg. But even if you eat zero purines, your body still makes 80% of the uric acid you have. So diet alone won’t cure gout.What will? Three things:

- Get your serum uric acid tested. If it’s above 6.8 mg/dL, you have hyperuricemia-even if you’ve never had a flare.

- If you’re on allopurinol, ask your doctor if you’re on a high enough dose. Most people need 300 mg or more. Don’t stop because you didn’t feel better at 100 mg.

- Start colchicine at the same time as your urate-lowering drug. It’s not optional. It’s essential.

If you’ve had tophi, or flares in more than one joint, your target should be below 5.0 mg/dL. That’s not a suggestion-it’s a medical necessity. Anything higher and crystals will keep forming.

The Future of Gout Treatment

New drugs are coming. Verinurad, a cleaner uricosuric, is in Phase III trials and could replace the risky lesinurad. Arhalofenate is being tested as a dual-action drug that lowers uric acid and reduces inflammation at the same time. And researchers are exploring genetic testing to predict who will respond to allopurinol versus febuxostat. Variants in the SLC2A9 gene, for example, affect how well your kidneys clear uric acid.But the biggest barrier isn’t science-it’s access. Pegloticase costs more than $16,000 a month. Insurance companies fight these prescriptions. Patients go through 10+ appeals just to get coverage. Meanwhile, generic allopurinol sits at $4.27 a month. We have a cure that costs pennies. But the system doesn’t reward it.

The real breakthrough won’t be a new pill. It’ll be a system that actually follows patients, monitors their labs, adjusts doses, and supports them through the first six months when flares are most likely. Until then, gout remains a disease of neglect-not biology.

Susie Deer

January 14, 2026 AT 09:40Allison Deming

January 15, 2026 AT 03:11TooAfraid ToSay

January 16, 2026 AT 10:14Dylan Livingston

January 17, 2026 AT 09:42Andrew Freeman

January 19, 2026 AT 03:22says haze

January 19, 2026 AT 23:46Alvin Bregman

January 21, 2026 AT 15:35Sarah -Jane Vincent

January 23, 2026 AT 15:23Henry Sy

January 24, 2026 AT 16:39Anna Hunger

January 25, 2026 AT 07:17Jason Yan

January 25, 2026 AT 15:33shiv singh

January 26, 2026 AT 22:58Robert Way

January 28, 2026 AT 13:58Sarah Triphahn

January 29, 2026 AT 03:04Vicky Zhang

January 29, 2026 AT 21:28