Generic Drug Supply Chain: How Medicines Reach Pharmacies

Every time you pick up a bottle of generic atorvastatin or metformin at the pharmacy, you’re holding a product that’s traveled through a global network far more complex than it looks. These pills aren’t just cheaper copies of brand-name drugs-they’re the result of a tightly controlled, highly fragmented system that spans continents, regulations, and profit margins. And yet, most people have no idea how they get there.

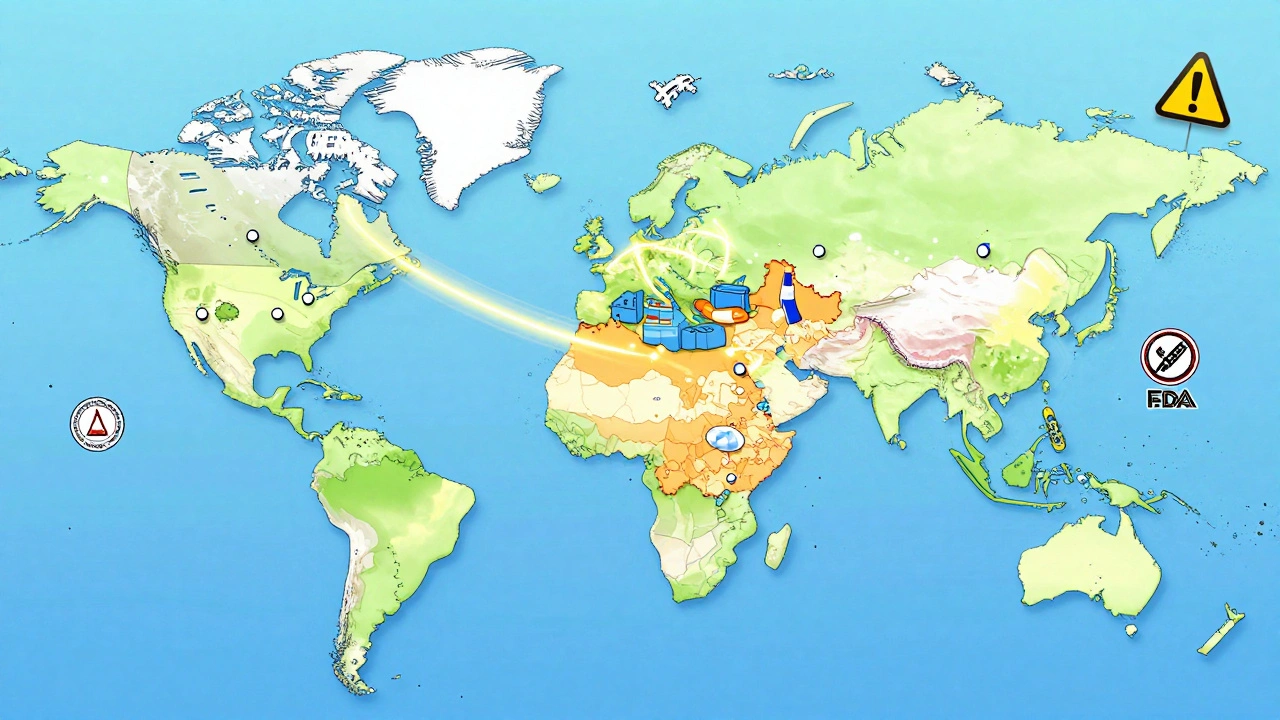

Where It Starts: The Global Hunt for Active Ingredients

It begins with something you’ll never see: Active Pharmaceutical Ingredients, or APIs. These are the actual chemical compounds that make the medicine work. For generic drugs, 88% of these APIs are made outside the U.S.-mostly in China and India. The rest come from a shrinking number of domestic facilities. Why? Because producing APIs at scale in countries with lower labor and regulatory costs is far cheaper. But this global setup creates serious risks. During the pandemic, when factories in India or China shut down, over 170 generic drugs in the U.S. faced shortages. The FDA inspected just 248 foreign facilities in 2010. By 2022, that number had jumped to 641-but it’s still not enough to keep up with the volume.From Chemical to Pill: Manufacturing and FDA Approval

Once the API is made, it’s shipped to a U.S.-based or international manufacturer who turns it into tablets, capsules, or injections. But they can’t just sell it. To get approval, they must file an Abbreviated New Drug Application (ANDA) with the FDA. This isn’t a full clinical trial like brand-name drugs need. Instead, they prove their product is bioequivalent-meaning it delivers the same amount of active ingredient at the same rate as the original. It’s a faster, cheaper path, but quality control is non-negotiable. Every batch must pass strict Good Manufacturing Practices (GMP) checks. That means testing for purity, potency, and stability at multiple stages. One failed test can hold up an entire shipment. And if the FDA finds repeated violations, the facility gets flagged-or worse, shut down.The Middlemen: Wholesalers and Distributors

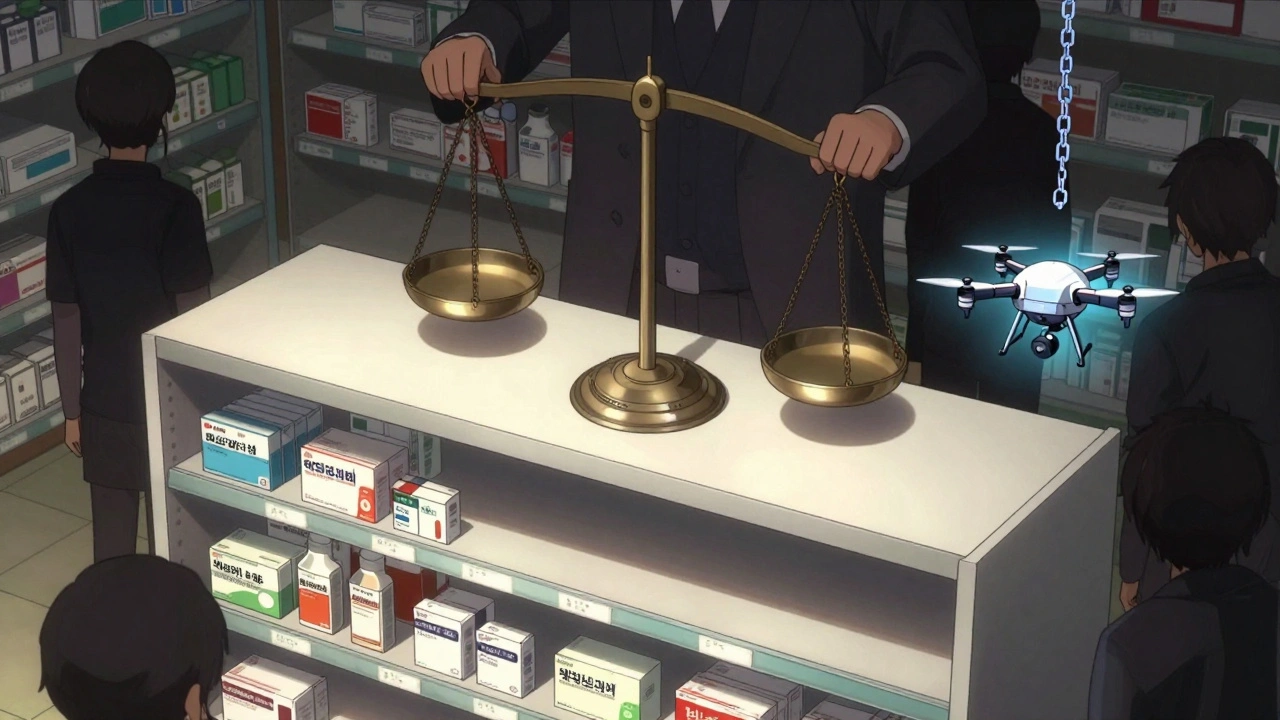

After manufacturing, the pills don’t go straight to your local pharmacy. They go to wholesale distributors. These companies buy in bulk from manufacturers and then sell smaller quantities to pharmacies. Think of them as the logistics backbone. They handle storage, inventory tracking, and delivery. But here’s the catch: they add their own markup. And unlike brand-name drugs, where manufacturers offer big rebates, generic manufacturers rarely negotiate discounts directly with pharmacies. Instead, pharmacies deal with wholesalers who offer “prompt payment discounts”-meaning if you pay fast, you get a slightly lower price. This system favors big pharmacy chains that can buy in massive volumes. Independent pharmacies? They’re at the mercy of these deals.

Who Sets the Price? PBMs and MAC Reimbursement

This is where things get confusing. You might think the pharmacy sets the price you pay. They don’t. It’s controlled by Pharmacy Benefit Managers, or PBMs. CVS Caremark, OptumRX, and Express Scripts control about 80% of the market. These companies negotiate with insurers and employers to determine what pharmacies get paid for each drug. For generics, they use something called Maximum Allowable Cost, or MAC. MAC isn’t based on what the pharmacy paid. It’s based on a blended average of what similar generics cost across all manufacturers. So if one company slashes its price, the MAC drops for everyone. Pharmacies end up getting reimbursed less than what they paid to buy the drug. A 2023 survey found that 68% of independent pharmacists say MAC pricing is below their actual cost-meaning they lose money on every generic prescription they fill.Why Generic Drugs Cost So Little (But Pharmacies Earn Even Less)

Here’s the real irony: generic drugs make up 90% of all prescriptions in the U.S., yet they account for only 23% of total drug spending. That sounds like a win-until you look at who actually profits. Generic manufacturers take home just 36% of the money spent on their drugs. Brand-name companies? They keep 76%. Why? Because brand manufacturers negotiate rebates with PBMs. If a drug has few alternatives, they can demand huge discounts from PBMs in exchange for keeping their drug on the formulary. Generic manufacturers? They rarely do this. They compete on price alone. So while you pay $4 for your generic blood pressure pill, the manufacturer might have made only $0.50 of it. The rest goes to distributors, PBMs, and middlemen.

Gilbert Lacasandile

December 10, 2025 AT 06:28Really eye-opening breakdown. I had no idea how thin the margins were for pharmacies. My local independent one just switched to a new wholesaler last month because they were getting crushed on MAC rates. They’re barely breaking even on generics now, which is wild considering how much we rely on them.

It’s like they’re running a charity while the big players take the profits.

Morgan Tait

December 12, 2025 AT 03:17Let me guess - China’s got the APIs, India’s got the pills, and the FDA’s got a spreadsheet with ‘maybe’ stamped on it. Meanwhile, your $4 blood pressure pill? The guy who made it got paid in ramen noodles and hope. This whole system’s one geopolitical tantrum away from collapsing into a pile of expired metformin.

And don’t even get me started on how PBMs are basically financial vampires sucking the life out of pharmacies. Someone’s gotta audit those contracts - with a flamethrower.

Katie Harrison

December 13, 2025 AT 15:48As someone who’s worked in Canadian pharma logistics, I can confirm: the fragmentation is insane. We see the same patterns here - except our government caps what PBMs can charge, so pharmacies aren’t losing money on every script. Still, delays from overseas manufacturers? Constant.

And yes, blockchain pilots are promising. One pilot in Ontario tracked a batch of generic metformin from a Hyderabad factory to a rural clinic - took 11 days, and we knew exactly where it sat in customs for 72 hours. Transparency helps, but it doesn’t fix the profit imbalance.

Mona Schmidt

December 15, 2025 AT 12:21The bioequivalence requirement for ANDAs is often misunderstood. It’s not just about the active ingredient - it’s about dissolution rate, excipients, even particle size. A pill that dissolves too slowly won’t be absorbed properly; too fast, and you risk toxicity.

Manufacturers must test every batch under multiple environmental conditions - humidity, temperature, shelf life. That’s why recalls happen: a single batch failing stability tests can trigger a nationwide alert. The FDA’s inspection numbers are still laughably low, but the technical bar for approval is absurdly high. It’s a paradox.

Guylaine Lapointe

December 17, 2025 AT 06:01Why are we even pretending this is a free market? It’s a cartel disguised as competition. Ten companies control 65% of the market, and they all know it. When one shuts down, the others quietly raise prices - just enough to stay profitable, but not enough to trigger scrutiny.

And don’t tell me ‘low prices are good.’ They’re not good if they mean pharmacies go under and patients lose access. This isn’t economics - it’s corporate sabotage wrapped in a ‘value’ label.

Sarah Gray

December 18, 2025 AT 20:02How quaint. You believe the FDA is a guardian of public health? Please. They approve foreign facilities based on paperwork submitted in Mandarin. The last inspection report I read from a Chinese API plant had ‘minor deviations’ listed as ‘dust on the floor.’

Meanwhile, your $4 pill? It was made by someone earning $2/day, shipped through three middlemen, and priced by an algorithm that thinks ‘profit’ is a verb. This isn’t healthcare - it’s supply chain performance art.

precious amzy

December 19, 2025 AT 15:41One might posit that the commodification of life-sustaining substances is the logical endpoint of late-stage capitalism’s colonization of the biological. The pill, once a symbol of therapeutic intervention, has been reduced to a fungible unit in a global ledger - its value determined not by efficacy, but by arbitrage.

Is it ethical to equate human health with wholesale pricing tiers? And if the system collapses under its own contradictions, who bears the moral burden - the manufacturer, the PBM, or the consumer who dares to ask for a prescription?

Maria Elisha

December 19, 2025 AT 20:18So… we’re saying generic drugs are cheap because everyone else is getting rich off them? Cool. I’ll just keep taking mine. 😅