Erythromycin vs Alternatives: A Clear Comparison

Antibiotic Selection Guide

Choose Your Scenario

When a doctor prescribes a macrolide antibiotic, many patients wonder if there’s a better option for their infection. You’ve probably heard the name erythromycin tossed around a lot, but how does it really stack up against other common choices? This guide walks through the key differences, side‑effect profiles, and practical tips so you can understand when erythromycin makes sense and when an alternative might be smarter.

What is erythromycin?

Erythromycin is a broad‑spectrum macrolide antibiotic that inhibits bacterial protein synthesis by binding to the 50S ribosomal subunit. First approved in the 1950s, it’s been used for respiratory, skin, and sexually transmitted infections. Because it’s a natural product derived from Saccharopolyspora erythraea, it’s often called a “classic” macrolide.

Why compare erythromycin with other antibiotics?

Doctors rarely stick to a single drug for every infection. Factors like dosing convenience, resistance patterns, and side‑effect tolerance all play a role. By laying out the trade‑offs, you can have a clearer conversation with your clinician and avoid surprises.

Top alternatives to erythromycin

- Azithromycin - a newer macrolide with a longer half‑life, allowing once‑daily dosing.

- Clarithromycin - another macrolide known for strong activity against Helicobacter pylori.

- Doxycycline - a tetracycline that works well for atypical infections and has good intracellular penetration.

- Clindamycin - a lincosamide useful for anaerobic bacteria and skin infections.

- Amoxicillin - a penicillin‑type beta‑lactam often chosen for ear, nose, and throat infections.

How these drugs differ: a quick snapshot

| Antibiotic | Class | Typical Dose (adult) | Half‑life | Common Side‑effects | Resistance Concerns |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Erythromycin | Macrolide | 250‑500 mg every 6 h | ~1.5 h | GI upset, liver enzyme rise | High in many Streptococcus spp. |

| Azithromycin | Macrolide | 500 mg on day 1, then 250 mg daily x 4 days | ~68 h | Mild GI upset, QT prolongation | Lower than erythro, but rising in Neisseria |

| Clarithromycin | Macrolide | 500 mg every 12 h | ~3-7 h | Metallic taste, GI upset | Similar to erythro, but better against H. pylori |

| Doxycycline | Tetracycline | 100 mg twice daily | ~18 h | Photosensitivity, esophageal irritation | Low for atypicals, higher for Staphylococcus aureus |

| Clindamycin | Lincosamide | 300 mg every 6 h | ~2.5 h | Diarrhea, C. difficile risk | Useful when macrolide resistance present |

Side‑effect profile: what to watch for

Erythromycin is notorious for causing stomach upset because it stimulates gut motility. You might feel cramping, nausea, or even a brief diarrheal episode. In rare cases, liver enzymes climb, so doctors often order a baseline blood test if you’ll be on the drug for more than a week.

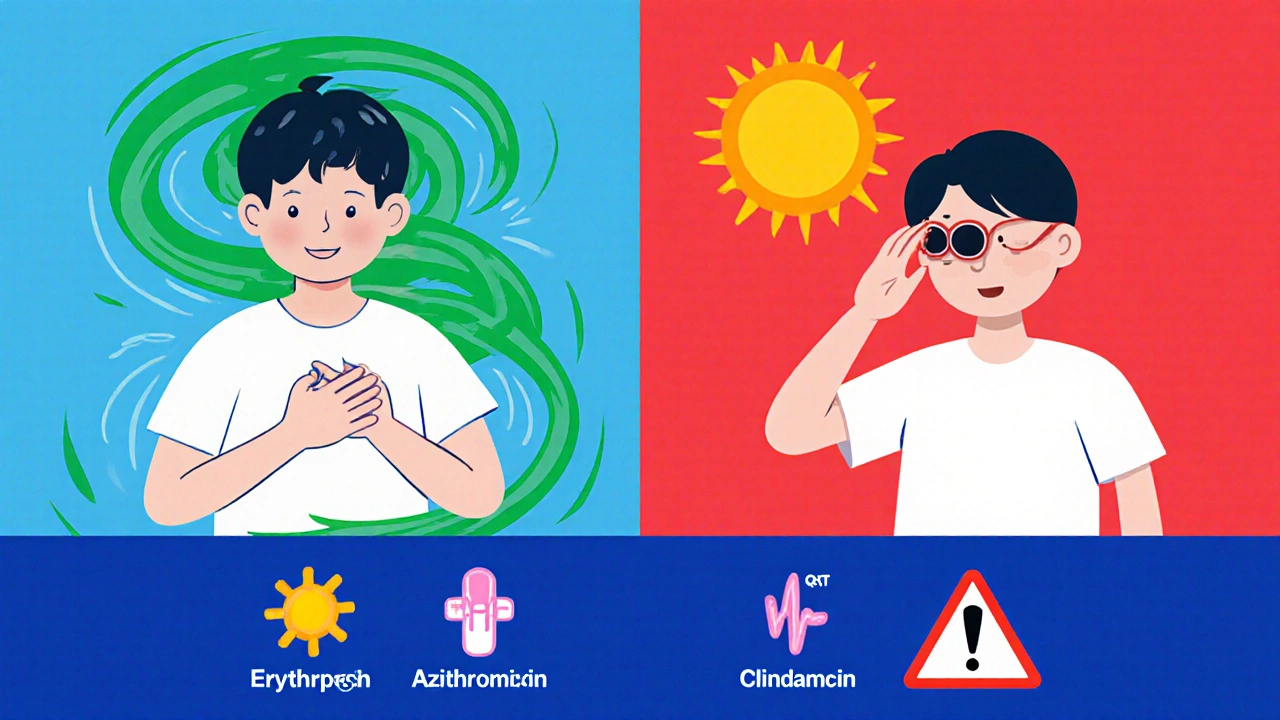

Azithromycin tends to be gentler on the stomach, but its long half‑life means it can linger in the body and occasionally affect heart rhythm (QT interval). Clarithromycin shares the GI upset vibe but adds a metallic taste that many find unpleasant.

Doxycycline’s biggest complaint is photosensitivity - you’ll want sunscreen if you’re outdoors. Clindamycin carries the highest risk of a serious gut infection called Clostridioides difficile colitis, which can be life‑threatening.

Pharmacokinetics made simple

Understanding how a drug moves through the body helps explain dosing differences. Erythromycin’s short half‑life (about 1.5 hours) forces multiple daily doses, which can be inconvenient. Azithromycin’s long half‑life (almost 3 days) lets you finish a full course in just five days, a big plus for adherence.

Clarithromycin sits in the middle, offering twice‑daily dosing but still requiring a full 7‑10‑day course for most infections. Doxycycline’s half‑life of roughly 18 hours allows twice‑daily dosing without the stomach‑ache punch. Clindamycin’s rapid clearance (2‑3 hours) keeps it effective but means you’ll need more frequent dosing.

When to choose erythromycin

Despite newer options, erythromycin still shines in a few niche scenarios:

- Patients who cannot take beta‑lactams due to penicillin allergy but need coverage for Streptococcus pneumoniae.

- When a clinician needs a drug that works well in acidic environments, such as stomach ulcers.

- In some low‑resource settings where azithromycin or clarithromycin are unavailable or too costly.

If you fall into any of these categories, discuss the dosing schedule and potential GI side‑effects with your doctor.

When an alternative is smarter

Most of the time, one of the newer macrolides or a completely different class will be a better pick:

- For community‑acquired pneumonia, azithromycin’s once‑daily regimen improves compliance.

- When treating Helicobacter pylori infection, clarithromycin is part of the standard triple‑therapy regimen.

- For atypical pneumonia (caused by Mycoplasma or Chlamydia), doxycycline offers excellent intracellular penetration with fewer GI complaints.

- If you have a history of C. difficile infection, avoid clindamycin and consider a non‑clindamycin macrolide.

Bottom line: making the right call

There’s no one‑size‑fits‑all answer. Erythromycin remains a solid choice for specific infections and when cost is a factor, but its dosing frequency and GI side‑effects often make azithromycin, clarithromycin, or doxycycline more attractive. The key is to match the drug’s strengths to the infection’s location, the patient’s medical history, and the likelihood of resistance.

Frequently Asked Questions

Is erythromycin safe during pregnancy?

Erythromycin is classified as Category B by the FDA, meaning animal studies have not shown risk, but there are limited human data. Doctors may prescribe it if the benefits outweigh potential risks, especially for infections where alternatives are unsuitable.

Can I take erythromycin with other medicines?

Yes, but erythromycin is a strong inhibitor of the liver enzyme CYP3A4. It can raise levels of drugs like statins, some anti‑arrhythmics, and certain anti‑epileptics. Always share your full medication list with your prescriber.

Why does erythromycin cause stomach cramps?

The drug stimulates motilin receptors in the gut, triggering stronger peristalsis. This effect speeds up gastric emptying, which can lead to cramping, nausea, or vomiting.

How long does it take for erythromycin to work?

Most patients notice symptom improvement within 48‑72 hours, though you should complete the full prescription to fully eradicate the bacteria.

Is antibiotic resistance a problem with erythromycin?

Yes. Overuse has led to high resistance rates in common pathogens like Streptococcus pneumoniae and Staphylococcus aureus. That’s why culture‑guided therapy is preferred whenever possible.

Amanda Vallery

October 24, 2025 AT 15:03Erythro works but the dosing is a pain and the stomack upset kills the vibe.

Lindy Hadebe

October 25, 2025 AT 13:16The guide glosses over real resistance data and leaves out the cost factor.

Ekeh Lynda

October 26, 2025 AT 10:30Erythromycin was discovered in the 1950s and it remains a staple in many formularies. Its mechanism involves binding to the 50S ribosomal subunit and halting protein synthesis. The drug is active against a broad range of gram positive organisms. It also covers some atypical pathogens. The short half life of roughly one and a half hours forces dosing every six hours. Patients frequently report nausea abdominal cramping and a metallic aftertaste. The motilin receptor agonism is responsible for the gastrointestinal motility increase. In contrast azithromycin boasts a long half life near sixty eight hours allowing once daily dosing. Clarithromycin offers a middle ground with a half life of three to seven hours and a strong activity against H pylori. Doxycycline, a tetracycline class, penetrates cells well and avoids the gastric irritation but brings photosensitivity. Clindamycin provides excellent anaerobic coverage yet carries a high risk of C difficile colitis. Resistance to macrolides has risen especially among Streptococcus pneumoniae and Staphylococcus aureus. Culture guided therapy can help avoid unnecessary macrolide exposure. Cost considerations remain important in low resource settings where erythromycin may be the only option. Ultimately the choice depends on infection site patient tolerance and local susceptibility patterns.

Mary Mundane

October 27, 2025 AT 08:43Bottom line: pick the drug that fits the infection and your tolerance.

Michelle Capes

October 28, 2025 AT 06:56Totally get the hassle of GI pain 😕.

If you’re worried talk to your doc about a probiotic or switching to azithro.

Dahmir Dennis

October 29, 2025 AT 05:10Oh sure prescribe erythro every time because why bother with modern pharmacology when you can hand patients a four times a day regimen that turns their stomach into a fireworks display. The joy of watching someone gulp down 500 mg every six hours while battling nausea is truly a testament to medical optimism. Meanwhile newer agents sit on the shelf laughing at the antiquated dosing schedule. If only we valued patient convenience as much as we love brand names. So yes keep the legacy drug alive if you enjoy watching people suffer.

Jacqueline Galvan

October 30, 2025 AT 03:23Thank you for highlighting those points.

In practice, azithromycin’s simplified schedule often improves adherence, particularly in outpatient settings.

Nevertheless, erythromycin remains valuable when beta‑lactam allergy precludes other options.

Tammy Watkins

October 31, 2025 AT 01:36Esteemed colleagues, the discourse surrounding macrolide selection warrants a theatrical yet rigorous examination. First, the pharmacokinetic profile of erythromycin commands respect due to its rapid clearance necessitating multiple daily administrations. Second, the gastrointestinal motility stimulation intrinsic to erythromycin inevitably precipitates patient discomfort, a factor that cannot be dismissed lightly. Third, the specter of resistance looms large, with Streptococcus pneumoniae demonstrating alarming prevalence of macrolide‑mediated mechanisms. Fourth, azithromycin, with its protracted half‑life, offers a symphonic cadence of once‑daily dosing that harmonizes with modern patient lifestyles. Fifth, clarithromycin, while potent against Helicobacter pylori, bears the burden of drug‑drug interactions via CYP3A4 inhibition, a veritable minefield for polypharmacy patients. Sixth, doxycycline’s intracellular penetration renders it a champion against atypical organisms, yet its photosensitivity side‑effect curtain demands vigilant sun protection. Seventh, clindamycin provides unparalleled anaerobic coverage but introduces the perilous risk of Clostridioides difficile colitis, a drama best avoided when alternatives exist. Eighth, cost considerations in resource‑limited settings may cast erythromycin in a heroic light, but such heroism must be weighed against adherence challenges. Ninth, the patient’s comorbidities, particularly hepatic dysfunction, influence the selection matrix profoundly. Tenth, clinical guidelines increasingly favor azithromycin for community‑acquired pneumonia owing to superior compliance metrics. Eleventh, the microbiological laboratory’s susceptibility data should steer therapy, rather than antiquated habit. Twelfth, shared decision‑making empowers patients to choose regimens aligned with their daily routines. Thirteenth, counseling on potential side‑effects, including motilin‑mediated cramping, mitigates unexpected adverse events. Fourteenth, providers should remain vigilant for drug interactions, especially when prescribing macrolides alongside statins or anti‑arrhythmics. Fifteenth, in the grand theater of antimicrobial stewardship, the optimal choice is the one that balances efficacy, safety, and patient adherence, securing a triumphant resolution for both patient and public health.

Carla Taylor

October 31, 2025 AT 23:50Yo I love how the post breaks down the options no fluff just facts.

Kathryn Rude

November 1, 2025 AT 22:03One must contemplate the epistemic underpinnings of such comparative matrices 😊 the author eschews nuance in favour of bullet points and thereby reduces clinical complexity to a superficial checklist which, frankly, does a disservice to discerning practitioners.

Jordan Levine

November 2, 2025 AT 20:16Patriotic physicians demand that we prioritize home‑grown antibiotics over imported novelties 🇺🇸💪 the reliance on foreign azithromycin undermines our medical sovereignty and breeds dependency on multinational pharma conglomerates 🙅♂️

Marilyn Pientka

November 3, 2025 AT 18:30From a pharmaco‑economic perspective, the cost‑benefit analysis of erythromycin versus azithromycin reveals a marginal utility curve where diminishing returns on compliance are offset by escalated adverse event indices.

Kester Strahan

November 4, 2025 AT 16:43Good point on the utility curve, just wonder how real‑world adherence data compares across different demographics.